Choosing to work with Hollywood’s unions is a major decision for any filmmaker or producer. There are pros and cons to joining or not joining. The choices you make at the start could have far-reaching consequences for your film.

If you make the wrong decision, you may find yourself in unchartered waters. Your crew members may start to dictate demands of their union. I have been on both sides of this and believe unions are a necessary part of filmmaking, so it is critical to understand how they operate.

Experience is the Best Lesson

1. Lessons from a guild

My father was a union man. In fact, he was a union organizer and representative for more than thirty years. I personally hold membership cards with three unions with varying levels of status.

But, I believe that unions are a double-edged sword.

As a producer and a recovering actor, I have been on the receiving end of a union’s might and wrath.

In fact, when I was much younger and still running to auditions, I received word that I had booked a prime TV guest-star role.

An hour later, I received a call from the producers. They informed me that I was a “must join.”

The catch?

I would need to join SAG before I started work.

This was a cost I wasn’t expecting. $1800 for a union I didn’t want to be apart of, for a union that didn’t help me find this job.

I walked into the union on my lunch break from my day job. I literally handed over my rent money. This was definitely not in my budget.

What did I get in return? A pen with the SAG logo.

And a membership card that didn’t come for another month.

All I remember thinking at the time was, “there ought to be a law against this.”

Union membership goes to anyone who lands a union gig.

It wasn’t so special to me after I landed a gig without a union. As an established actor, I am sure there are ample reasons to join the union. As a new actor with very few credits, the union was a cruel joke that prohibited my choice of jobs and demanded loyalty.

Related Posts

experiences with reps

2. Union representatives

As a producer, the Screen Actors Guild was also a thorn in my side.

Back in 2013, I was working as a line producer and production manager on my third feature film. It was then I learned that the union could make things difficult just because they wanted to.

During the middle of the shoot, the SAG union representative briefly lost our production payroll. They claimed we never sent it to them.

Let’s just say, I did not take it well. Neither did our production accountant. And hell hath no fury like a production accountant scorned.

I received a voicemail from our union rep. Let’s call him Charles Etta. Charles Etta said he didn’t have our payroll. Charles Etta threatened to pull all of our Screen Actors Guild cast members and background, unless he received the payroll by noon.

It was 10 am.

It just so happened that our accountant had dropped off the payroll herself that week, in person. But, Charles Etta still claimed he didn’t have it.

In no uncertain terms, he was going to shut me down for this grievance. It wasn’t just me or my production he was threatening.

He was threatening the livelihood of the eighty-five people employed on the film. He was threatening eighty-five people, who were looking to me for their pay, their schedules and their source of income for the next month and a half.

Eighty-five people who were making significantly less than the members of their union. I turned to Kelvin Ho, my coordinator, and asked him to fax over the drop-off receipt and the payroll back up.

Production Coordinator, Kelvin Ho still managed a smile

I could show that we had done our parts correctly. I put Ms. McGraw, our production accountant, on the phone. She told me not to worry she could have the payroll re-submitted in no time.

Sweet Sue McGraw would never let me down. I trusted her.

About thirty minutes later, Sue called back. She had been on the phone with Charles Etta and her assistant and reception. They found our payroll envelope at reception and we were fine.

But...

We didn’t get an apology. We got silence.

An hour of stomach-churning stress, in the middle of a production with children, animals, and a first time director, and the union representative didn’t even have the courtesy to call back and tell me personally that we wouldn’t be shut down.

At the end of the production, with a stiff drink in my hand, I wrote a strongly-worded letter to the Screen Actors Guild. I never sent it.

What was even worse? The pettiness continued.

On the very same production, the Screen Actors Guild visited to take stock of the production. They again tried to raise the level of bile in my stomach.

After a weekend where I had to replace our First Assistant Director, I was informed by one of my awesome background actors that a SAG rep was on site.

The rep spoke to the background and some of the talent.

Just after lunch, the SAG union representative asked to speak with me.

I could feel the production manager senses tingling. Today was not the day for this, and I was not in the mood.

The union representative was cordial enough, but…

Apparently, the craft service table set up for the background talent was not sufficient enough for the Screen Actors Guild.

There could be no distinction between what was available for the talent, background talent and crew.

We rectified the situation, but the bad taste of the union rep looking for grievance remained. In the mortal words of Charlie Brown, “Good grief?”

Related Posts

Do Your Homework First

3. Understanding grievances

The Screen Actor’s Guild is not the only union that I have had the pleasure of working with.

On the same low budget film that I thought was going to be non-union, I realized what I want and what I will receive are very different things.

In the beginning, there was talk of joining IATSE for the below the line positions.

UNION GRIEVANCE DEFINITION

A union grievance is a claim by a union that an employee has notified the union that a production company has misrepresented itself in hiring or production practices. Grievances protect employees from the decision or practices of film production entities and ensure certain benefits to its members. Grievances can be made by employees or the union itself.They were fined 8 grand. But this was still less than the cost of keeping the location and additional crew for the day.

This is not always the case.

In fact, when a union grieves, it’s usually to cover the cost of lost union wages, pension and health, and other costs such as the union reps time and visit.

When It's No Longer a Grievance

4. Being flipped and union signatories

When a grievance is filed, it is usually because there is a very good reason.

It also means you have someone on your set who knows that there is something that doesn’t gel with the collective bargaining agreement.

One example of this is the presence of a non-union worker on a union job. This is the most common.

Teamsters know when they aren’t being hired and will promptly call their union representative.

Another reason is the union status of one department is different from another, i.e. the Casting Director is union, but the Grip and Electric department are not.

We were told that it was possible to join on the lowest budgeted tier. We did have a very meager budget. Most of it was already allotted to the name talent.

But in order to get the talent that the Casting Director brought onboard, we would have to join the Casting Director’s Union. IATSE Local 399 handles casting directors.

Guess who didn’t understand that signing with one branch of IATSE meant that you were signing with all the branches?

The producers.

But, I did as asked. I signed the paperwork and thought nothing of it, until...

Two weeks into production, one of our crew members receives a call from his union representative who informs him that they’ll be making a visit to our set.

They were going to come and take a look at the production. Then, they were going to need to speak to me. Oh. Good. Grief.

I watched from behind a grip as she came on set.

I tried to rationalize her being on my closed set in the middle of the San Fernando Valley.

The union rep was just doing her job.

There was no reason for me to be angry or act rude.

I knew it would be a possibility that they would make an appearance. But we had nothing to hide, least of all money.

The rep realized pretty quickly that there wasn’t enough union personnel on the set to make it worth her while to cause problems for our small indie film. But we were duly intimidated and warned. I would never make this mistake again.

More recently, a commercial producer and personal friend of mine told me the tale of her trip into the land of union grievances.

She worked on a union production for a very well-known shoe brand.

She had a mild but telling run-in with the Art Director’s Guild, IATSE Local 800.

Because she had double booked for another commercial, her usual staff of union workers were not available to strike a set. She brought in a couple of non-union workers and crossed her fingers. Guess what happened next?

You guessed it. The union representative showed up and told the producer’s they had to grieve.

Had the employers of past generations dealt fairly with their men there would have been no unions.

— Stanley Baldwin

Usually, when a line producer or production manager is notified that a grievance is filed, time is of the essence.

If the production is already union, then it is usually a fine that occurs. Sometimes the fine will be less than the cost of hiring union workers. Other times, it will be significant enough that someone will have to shoulder the blame.

I have an understanding that the Art Director’s Guild will give a production around four to eight hours to become compliant with the agreement, or they will pull their members.

Other unions give the same amount of time.

The union representative will make a visit to the set for a quick assessment. They usually do so without any disruption but will begin speaking with the crew. Often, they will already have a call sheet and know the members of their union who are working the job.

After getting a sense of how many union workers there are on the set, the union representative will have a meeting with the union members.

The rep informs them that there has been a grievance filed. The production displays enough money and members to be signatory to union standards.

Signatory Definition

what is A Signatory?

A signatory is someone who signs a document and is subject to it. The term signatory usually refers to a company that is signed to agreements of one or more of the unions whose members work on the production of advertising and entertainment content. Companies signed to union agreements are also called “Signatory Producers."

If the production chooses not to become signatory, then the union members vote to collectively walk.

In most cases, all of the other unions represented on the production will cease to work, in solidarity.

Union representatives can start out like Sally Field in Norma Rae

Before you make a decision on joining the union in order to keep your production running smoothly, you must consider all the reasons you didn’t join the union in the first place.

But what you do before or after will be the same.

“GETTING FLIPPED” DEFINITION

WHAT DOES IT MEAN TO GET FLIPPED?

“Getting flipped” is film industry-speak for the process of becoming a union production in the middle of a non-union shoot. A union representative has assessed a production’s status, expenditures, and length of production and found that the production should be meeting the standards of the collective bargaining agreement. The offended union will pull its’ members unless the production company, or production itself, becomes a signatory to the collective bargaining position for that union.Rather than shut down production, the filmmakers or production entities must commit to union rules regarding pay, benefits, meals, and pension.

Related Posts

get to work

5. Stay organized when you’re flipped

Once you agree to the terms of the collective bargaining agreement, you’ve been flipped. You are now a union production.

Now it’s time for the producers to break out the full budget and either make it happen or find replacements.

Any producer worth their salt will have planned for this eventuality.

You will need a new budget, schedule, production calendar, shot list and crew list. The last thing you want is to budget non-union and then get flipped in the middle of your shoot.

You can go slightly over budget by signing a union agreement, or you can go way over budget by having your production shut down and starting over.

But, budget for a union crew at the tier that you can afford. This means you will definitely have to cut cost somewhere. Maybe it’s equipment, maybe it’s location, but it must be done.

You will definitely need to reschedule your shoot should this happen. Try cutting unnecessary shots. Combine light days.

Anything to re-allocate your budget and schedule.

Did You Know?

I'm from a working-class background, and I've experienced that worry of not having a job next week because the unions are going on strike.

— Annie Lennox

Sit down with your heads of department and come up with a plan.

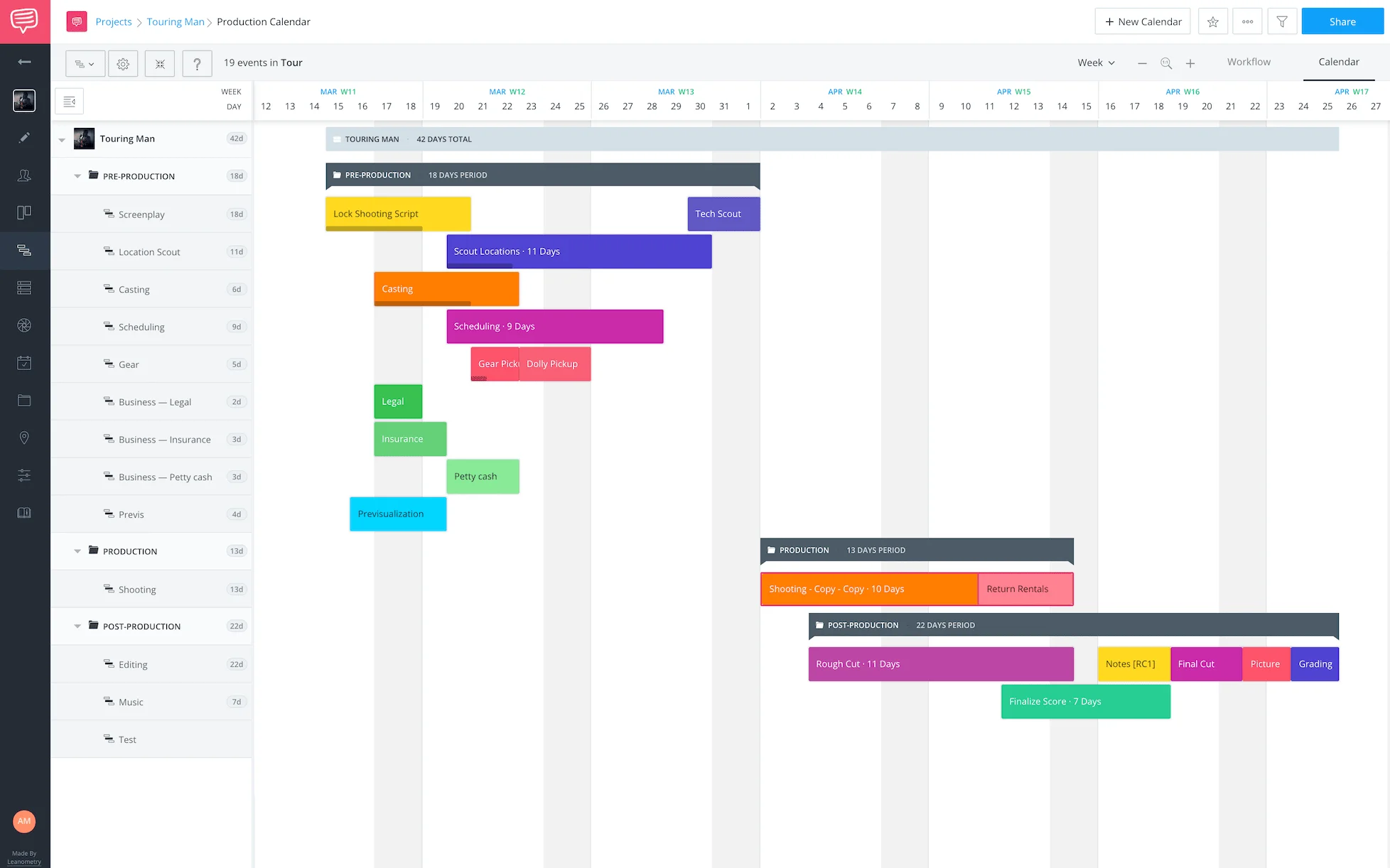

Start by looking at your production calendar.

This is where it is essential to have a production management software like StudioBinder.

You will have to have every bit of information at your fingertips in order to truly assess where you are in production and how you will proceed.

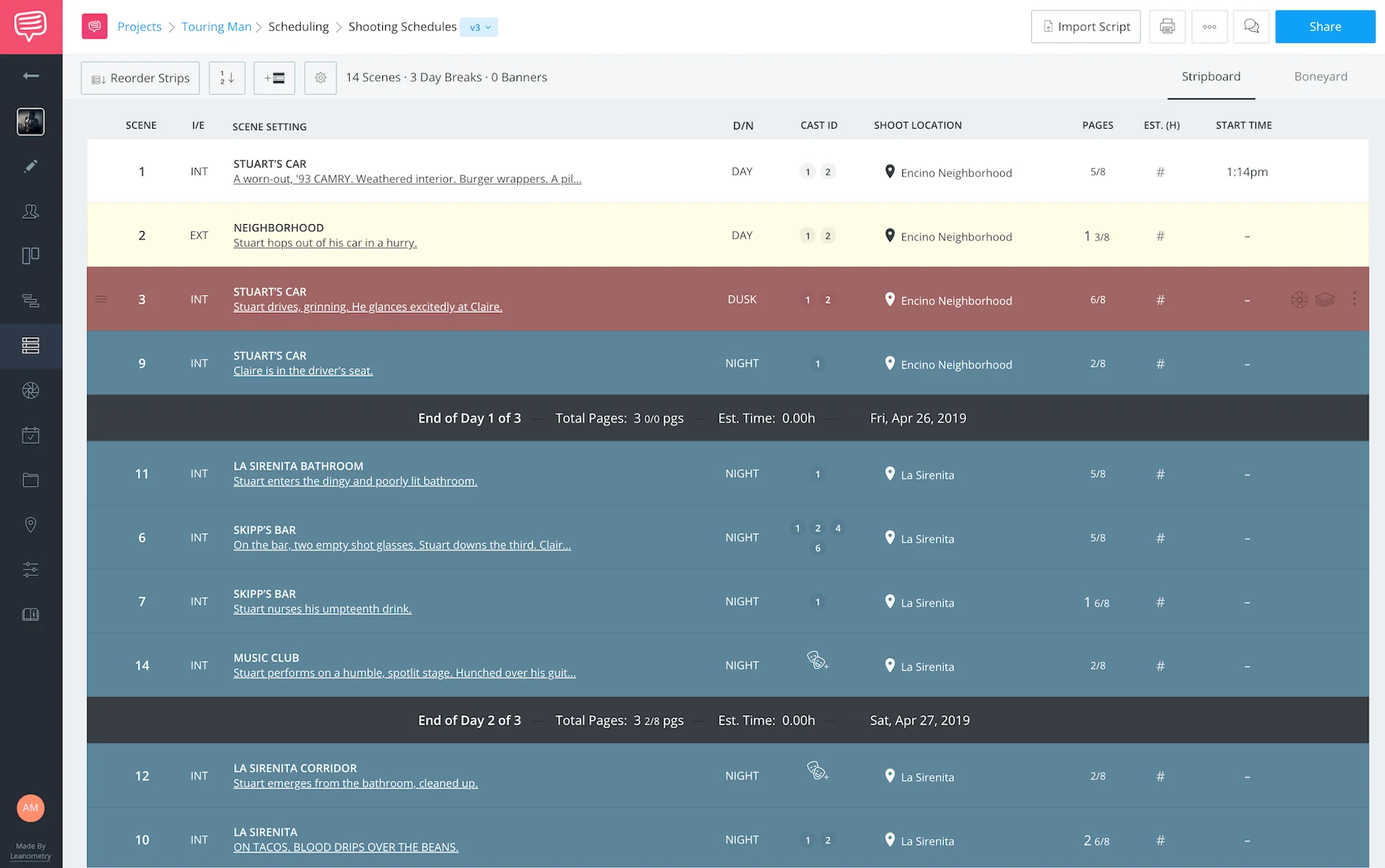

Once you get this macro understanding of what needs to be altered, use StudioBinder's drag and drop schedule for the day to day tasks. It will come in handy in recovering time lost and managing future time.

The software streamlines the entire production process, and keeps your team connected. So when you have to deal with union changes to your calendar or schedule, everyone is made aware at the same time.

Do yourself a favor and have production management solution like StudioBinder on hand to tackle the new world of union rates and schedule changes.

You may have to limit the number of production days. You could also reallocate some of your post days to production.

One way to cut cost is cutting that huge crane or aerial shot. To figure out a substitute, take out your shot list and start picking it apart.

The next task on your list after you’ve been flipped is taking stock of the entire crew. Grab your crew contact sheet and assess if you will need everyone that you’ve hired. You cannot fire everyone without cause, but you can trim the number of days of work. This is true of talent and crew.

Ideally, these steps happen before you make the decision to go union.

But the unions will try to work with you and even propose solutions that could prove beneficial.

You may not have to pay back wages depending on the union tier you join. But we’ll get to tiers in a moment.

Just know that the unions aren’t there to terrorize indie filmmakers, though it often feels this way. Many producers try to check the status of their crew before production begins. Union workers will take a non-union job in order to get the production flipped.

Unethical? Yes.

Uncommon? Not at all.

Nobody wants to strike. Any uncertainty in filmmaking is stressful. When you are depending on work to pay bills or feed your family, it is even more stressful.

Trust that your crew wants fair work conditions and a paycheck. They don’t want to be involved in anyone’s picket line.

Related Posts

becoming signatory

6. Choose wisely when joining a union

Working with films of a certain budget dictates your union status in many cases.

What is considered ultra low-budget, low budget, or standard theatrical is clearly defined by all of the unions you may choose to join. But, filmmakers have several choices to make when choosing to join a union or not.

One of the most important decisions to make is which unions to pick. Let’s look at which union and which tiers won’t bring the tears.

SCREEN ACTORS GUILD

If you are able to, and you are, make your project SAG signatory.

Why?

If you want to get name talent you must become signatory to the actor’s guild. If you want actors of a certain level it may be beneficial to go with the low budget agreement. SAG has several contracts to choose from. The SAG New Media Agreement, Ultra Low Budget, Low Budget, Television, and Theatrical all have very specific terms for use of SAG actors.

But, there is definitely something for every level of film production.

Yes, there will be a constant set of eyes looking over your shoulder. Yes, there will be a bond that will be a considerable part of your budget. Yes, there will be rigid rules to follow.

But you will have access to the top names in the business.

Once you make the choice which contract is best for you, know that there are people who are very well paid to find out if your budget and your crew are worth the union's attention.

IATSE

IATSE is a union that covers many positions on a film set.

From Casting Directors to Grips and Production Designers, the union’s reach is nearly all-encompassing. So if you have the resources, by all means, try to work with the union.

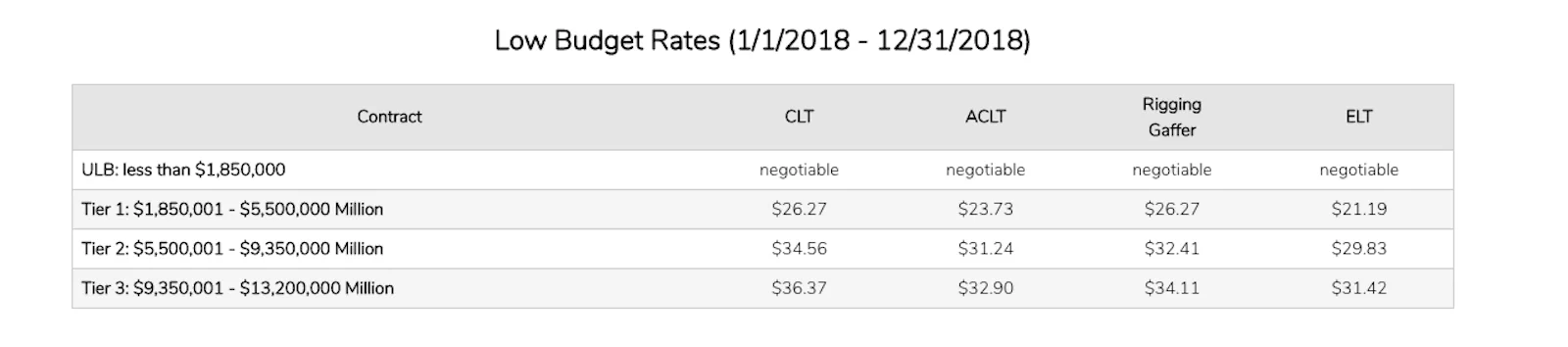

IATSE has several tiers in their collective bargaining agreement that allows low budget filmmakers to become signatory to the union.

Tier 1 is for films budgeted between 1.85 mil. and 5.5 mill. Still hefty sum for independents, but if you have a budget in this range, IATSE assumes you can pay your crew what they, and many others, have agreed is fair.

IATSE Tiers has something for everyone?

I have even heard that there is a Tier O which would be the IATSE version of the SAG New Media Contract. But, good luck getting the Grips and Gang Boss to work for minimum wage.

THE DIRECTORS GUILD

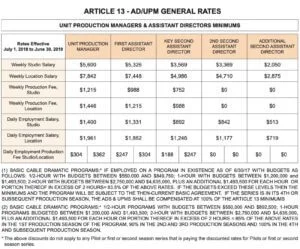

The Director’s Guild of America is another union that will find you if they have people working on your set. The DGA covers the film director, of course, but there are others they protect as well.

General rates

The Production Manager, 1st Assistant Director and the 2nd Assistant Directors may be covered by the union.

There is a gray area here. With the exception of the 1st AD, these positions don’t necessarily have to be in the union, even if the director and the entire rest of the crew are members of the unions.

But, if any of these positions are staffed by those in the unions, and the production itself is non-union, the DGA will find out and force their members to walk. It happens all the time.

THE WRITER’S GUILD

A strike can be devastating to every member of your film crew. A strike is devastating to the entire industry. There are some who say the industry never recovered from the Writers strike of 2008.

If your crew decides to set up barricades to force your production to go union, this is the worst-case scenario for all parties.

No one wants the lingering ill-will that a work stoppage instills.

Not only are time and money at stake, but relationships with future crew are at risk of being irrevocably broken.

On one hand, the crew members knew it was a non-union gig when they signed on. On the other hand, the producers should know when and where to cut costs in order to get the best crew possible.

Filmmaking is, at its core, about the art of compromise. That compromise should begin when you start to budget for the crew.

The last strike in the film industry was in 2008. It lasted for 100 days.

The Writers Guild and the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers were at odds over shares of profits generated by film, television, and new media.

Productions left Los Angeles and New York in record numbers.

While some production never returned, film centers like Toronto, Vancouver, and New Orleans, continue to boom 10 years later.

SHARKNADO Case Study

When Sharknado was grieved?

After the success of the first and second installments of the god-awfully, splendid SHARKNADO, producers SyFy and The Asylum went in for a third film. But, the producers chose to go non-union.

As the film went into production, about 40 members of the production team voted to go on strike. They demanded the film flip. The crew wanted the benefits that union membership insured. The producers fired the entire crew and hired replacements.

The union made calls to union and non-union crew members asking for their support of the strike. When the production moved to the East coast, IATSE made sure that the union crew there supported the strike.

The Asylum accused the union of mob-like tactics and refused to be “bullied” into unionizing . But, the producers did not cave. They finished the shoot.

What did the producers do?

- Re-wrote existing scenes

- Extended their production schedule

- Scaled back the scope of the entire production

The next 3 installments of the film were all highly successful, non-union productions. Unions are a part of the fabric of American democracy in so many ways, but ultimately when producers and workers are not working together, any film suffers.

It is only a matter of time before any successful producer will encounter the question of whether or not to make their production union, or not.

No matter what my personal reasons may be for my own position on whether or not to join, the union is there for a reason.

Make sure you have all the elements of your production in order so you avoid grievances, and have a successful production. Use your calendar to stay on track. If it does come time to join a union, now you can make an informed decision.

Related Posts

up next

Stepping up into a new position

Whether you are moving up the corporate ladder or are being thrusted into your bosses job, stepping into a new position can be harrowing. Especially in Hollywood. Fret not.

There are ways to make the adjustment that won’t make you pull your hair out. Master the move with a few practical (and psychological) steps you'll be grateful to know. There's no reason you can't enjoy your new role. Find out how, below.