Animation takes patience, attention to detail, boundless creativity, and more patience. The beauty of the artform is that, if you are willing to put the work in, there is no image you can’t create, no world you can’t immerse your viewer into. And yet, despite its endless possibilities, most narrative animators follow a certain set of rules. These rules are known as the 12 principles of animation.

What are the 12 principles of animation

Defining the 12 principles of animation

The 12 principles of animation were outlined decades ago (and in use for even longer than that). Yet they are still just as important today as they were when they were conceived.

ANIMATION PRINCIPLES DEFINITION

What are the 12 principles of animation?

The 12 principles of animation are a set of animating guidelines developed by Disney animators in the 20th century. These principles were codified by Disney alums Ollie Johnston and Frank Thomas in their 1981 book The Illusion of Life: Disney Animation. Because Disney’s animation style was so influential—and traditional animation became the dominant approach of the 20th century—animators everywhere use these principles in their work.

Though traditional animation has largely been replaced by 3D computer animation, Johnston’s and Thomas’s principles remain applicable.

The 12 Animation Principles:

- Squash and stretch

- Anticipation

- Staging

- Straight ahead and pose-to-pose

- Follow through and overlapping action

- Slow in and slow out

- Arc

- Secondary action

- Timing

- Exaggeration

- Solid drawing

- Appeal

These rules can apply to all types of animation and have done so for decades. For a quick refresher on the history of animation and its various types, check out this video.

History and Types of Animation • Subscribe on YouTube

We’ve included a collection of these principles using StudioBinder’s storyboard software. Click the image link below to see them all and download a PDF for future reference:

12 Principles of Animation Collection

Now that we know how the 12 principles came about, let’s look at each one of them a bit more in depth.

First Principle of Animation

Squash and Stretch

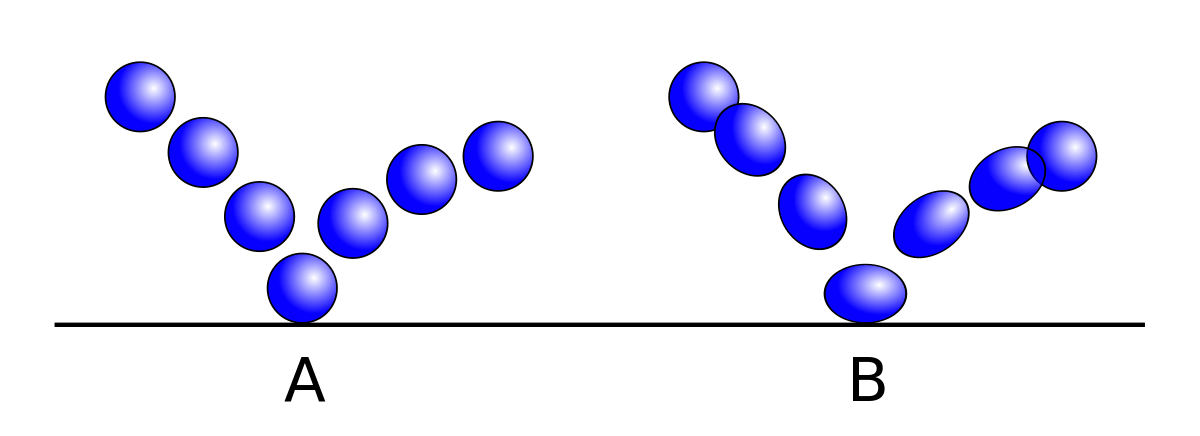

Squash and stretch is intended to give weight and malleability to objects. Think about it: if your animated object remains a constant, rigid shape throughout its movement, it’ll look unnatural.

Squash refers to when an object stops or hits something — it compresses slightly. Stretch, on the other hand, is when an object is speeding up.

Squash and stretch • Animation principles

There are a couple rules for squash and stretch. The object should never change volume. In other words, if it gets wider, it should also get shorter. If it gets taller, it should also get thinner. Second, the more you squash and stretch, the softer the object will appear, and vice versa.

The 12 principles of animation for realistic movement

Anticipation

How do you throw a football? Do you simply raise your arm and jerk it forward? If you answered yes to that question, you are likely not throwing your football very far. A throw requires a wind up – you bring your arm back so that you can get propulsion behind your movement.

Anticipation in action • Animation principles

This is the central idea behind anticipation: it’s the preparation before the action. And we’re not just talking about throwing balls. If you really pay attention to how things move (and Disney animators did), you’ll notice that almost all movement has an anticipation, even if it’s nearly microscopic.

What are the 12 principles of animation

Staging

Staging is a concept Johnston and Thomas borrowed from live-action filmmaking (which borrowed the concept from theater). Staging refers to how you direct the audience’s attention in a frame.

As Johnston and Thomas describe it, it’s essentially synonymous with mise-en-scène. Where are objects placed in the frame? What are lighting, color, and setting considerations? Where is the camera placed?

All of these decisions will help guide the viewer’s eye. Notice how our eye goes to the two dancing lovers in this still from Sleeping Beauty:

Sleeping Beauty staging • Animation basics

Different Animation Principles

Straight ahead action and pose to pose

This principle refers to how an animator actually animates. With straight ahead action, an animator is going frame by frame sequentially. With pose-to-pose, the animator will draw out the key poses that need to be hit, and then draw the in-between frames (also known as tweening).

Straight ahead is better for fluid, unpredictable movement. This might be fire, water, smoke, etc. The variation from frame to frame will take an animator to unexpected places.

Pose to pose is a bit more common because it lets an animator plan out how they want a movement to look. In other words, they have more control.

Pose to pose to pose • Animation basics

In computer animation, pose to pose utilizes key frames, and the computer will often automate the in-between frames for the animator.

Related Posts

Elements of Animation Character Performance

Follow through and overlapping action

Disney animators spent a lot of time studying how things move in the real world. Walt Disney himself would set up physics classes for his animators so that they could more fully understand the science of movement.

He even brought a deer onto the studio lot when the animators were working on Bambi, as this behind the scenes doc describes:

Bambi BTS • 12 animation principles

One of the main lessons the animators learned was that of inertia. When something starts moving, it doesn’t stop on a dime – its different elements will slow at different rates.

In other words, pieces of clothing on a character, or other looser items attached to them, will drag behind them and keep moving after they’ve stopped. Take a look at the jowls of this dog:

Follow through • Basics of animation

Both his floppy ears and cheeks drag behind as his head turns, and follow through once his head has stopped. Look at the costume movement in this sequence from The Emperor's New Groove:

Follow through • Fundamentals of animation

All this movement at all these different speeds is referred to by Disney animators as overlapping action – various things are happening at once.

Another sub-point for this principle is that of the “moving hold.” This just means that a character should never be totally still: they breathe, shift, blink, etc. even when standing still.

Animation Principles & Speed

Slow in and slow out

Slow in and slow out is directly linked to our previous principle. A character doesn’t just start moving at a consistent speed, and they don’t stop on a dime.

Slow in and slow out • Basics of animation

Rather, objects need time to speed up and slow down. Thus: slow in and slow out. Practically, this means there need to be more frames at the beginning and end of a movement than in the middle.

Related Posts

Rules of animation & physics

Arc

Perfectly straight lines are very rare in nature. When Disney animators studied movement, they realized that things didn’t move linearly from point A to point B. Instead, they discovered, movement typically happens in arcs.

This lesson can be applied to movements big and small. Note the movement of Basil’s head in this scene from The Great Mouse Detective – it’s all small arcs.

Arcs • Fundamentals of animation

Rules of animation for realism

Secondary action

Say you want to draw a character running. What would need to be animated? The first thing that probably comes to mind are probably the legs.

But no one runs with only their legs. They pump their arms. Their head bobs. They breathe heavily.

Secondary action in running

All of these movements are referred to by Johnston and Thomas as secondary action. Secondary action supplements the primary movement without distracting from it.

If a character is admiring a skyscraper, for instance, the primary action would be their eyes looking up. A secondary action may be the drools sliding out of their gaping mouth.

Animation fundamentals

Timing

The principle of timing refers more directly to the mechanics of animation. The core of the principle: the number of frames a movement is given dictates how much time a movement will take.

With timing, physics should be taken into account, of course, but so should emotion. Go back to our skyscraper admirer. We’d probably want that movement to be slow to highlight the awe the character feels.

The number of frames is only one of the considerations within timing. An animator must also decide on how long to hold on each frame. Animating on 1’s refers to animating a new image on each frame. Animating on 2’s (arguably the most popular approach for traditional animation) is when each drawing lingers for two frames. Animating on 3’s can be found in much of anime, and is when an animator draws a new image for every three frames.

Here are 1s, 2s, and 3s compared:

Timing • Disney’s 12 principles of animation

Disney animation fundamentals

Exaggeration

So far, we’ve focused a lot on imitating reality. But why animate if you’re trying to perfectly mimic reality? The beauty of the medium is that you can heighten reality. This is where exaggeration comes in.

A character is shocked? Put their jaw on the floor. A character is crying? Have waterfalls spouting out of their eyes. Is your character attracted to someone? Well, you can do this:

Howlin’ wolf exaggeration • 12 principles of animation examples

A quick tip for exaggeration: the quicker a movement is, the more exaggerated you can get, since it will take more to register with the audience.

Elements of animation

Solid drawing

This is one of the principles which is slightly less relevant with today’s 3D animation. The idea with solid drawing is that even though you’re drawing 2D characters, you need to take into account 3D space.

For Johnston and Thomas, this meant animators should study classical solid drawing before getting into the business. They argued that this background was crucial for a dynamic animator.

Bugs Bunny at all angles • 12 principles of animation examples

Within their solid drawing principle, the duo also discourage “twins,” referring to characters that have identical left and right sides. Movement shouldn’t mirror, and neither should a character's looks. Again, this is all in reference to the real world – perfectly symmetrical movement doesn’t feel organic.

Elements of animation for characters

Appeal

Appeal refers to the charisma of a character and their design. There’s no one way to do this, but in essence, a character should feel real and visually interesting. This often requires a ton of trial and error. Take, for example, Hayao Miyazaki’s Totoro.

The development of Totoro

Johnston and Thomas recommend giving likable characters round and childlike faces, but even this can be subverted. What’s important is that a character draws an audience’s eye. Use exaggeration, play with shapes and proportions, anything to create something original and captivating.

As this last rule illustrates perhaps the most, animation is an extremely varied art form, and constricting it with rules may seem counterintuitive.

But the 12 principles of animation can be a guide to get started, and to quell any frustration for a young animator wondering why their cartoons don’t look like The Lion King.

Related Posts

Up Next

Pre-production in animation

Do you have the 12 principles of animation down? Are you ready to make your animated movie? Then it’s time to learn about all the work that goes into an animated film before the pen hits the paper. Take a look at our step-by-step guide to pre-production in animation.

Up Next: Animation pre-production →

Showcase your vision with elegant shot lists and storyboards.

Create robust and customizable shot lists. Upload images to make storyboards and slideshows.