Narrative films are made up of scenes. It should come as no surprise that a screenwriter needs to know how to write a scene. Every great scene carries emotional weight, character change, and story propulsion. If you can’t write a good scene, you can’t write a good movie. So, what are some of the fundamental elements of a great scene? How can you incorporate them into your script? Time to break down how to write a scene, and look at some scene examples.

Watch: How to Write a Scene — 4 Elements Explained

How to Write a Scene Setting

What is a scene?

You may be rolling your eyes at this question. But the answer is a bit more complex than you might think.

Scenes are the building blocks of a narrative film. In his screenwriting book Craft of Scene Writing, Jim Mercurio defines a scene as “a small unit of story, unified by time and space, which encapsulates a single action and culminates in a change. The change should involve both the story and the character.”

Let’s take a look at this scene from Alexander Payne’s Election:

Election • Writing a scene example

The sequence is unified by space and time: it’s a continuous conversation in a classroom. The single action is the argument between Tracy and Jim. The change is that by the end of the scene, the two are openly hostile to each other: the battle is on.

We can break down scenes in two different ways. The first is by looking at them like their own short films, with a beginning, middle, and end.

Tracy and Jim are seemingly on the same side; they both want to catch the culprit (or so Tracy thinks). The middle is Jim starting to lecture Tracy on the perils of doing anything to get ahead.

The end is Tracy flipping the script and threatening Jim when he’s overstepped his bounds. It’s a strong character turn that illustrates timeless fiction writing tips—use conflict to reveal true intentions.

We can also separate a scene into beats. A beat is a small emotional or tonal change within a scene. Think of it this way: a beat is to a scene what a scene is to a film.

We can see very clear beats in this iconic scene from Goodfellas:

Goodfellas • How to write a scene

In the first beat, Tommy is having a good time, telling everyone a funny story. Everyone’s relaxed. In the next beat, Tommy shifts dramatically when Henry calls him funny. All of a sudden, the mood is tense.

When Tommy reveals he’s joking, we segue into the next beat, and everyone is feeling good again. The sudden shift in point of view—from camaraderie to fear—keeps the audience on edge, revealing how dangerous Tommy truly is. When the restaurateur interrupts the conversation, we move to another beat — Tommy’s angry again. We end the scene on a beat somewhere in the middle of the extremes. Everyone’s aware that Tommy’s in a dangerous mood, but they’re laughing along.

By having such clear beats, Martin Scorsese emphasizes Tommy’s temperamental nature and shows how to make a scene unpredictable yet grounded in character.

Let’s look at how we can use beats to structure a scene.

Related Posts

How to Write a Scene That Works

Scene structure

Scenes can take many shapes and sizes, but understanding scene structure is what separates a good scene from a forgettable one. If your goal is to make a scene that truly connects with the audience, structure is everything. Learning how to create a scene that blends conflict, pacing, and change will give your story momentum.

If you want to make a scene that resonates, start by breaking it down like a miniature story—with a beginning, middle, and end. But there are a few guidelines to scene structure that can be helpful to any screenwriter.

As we noted above, it’s useful to think of a scene as a short film. This means that we can think of the structure similarly. Let’s use the opening scene of Jaws as an example:

Jaws opening scene

It’s an iconic sequence, and one which has a structure that mimics that of a movie.

1. Establish the scene

First things first, we should understand what’s going on in a scene. Maybe not immediately (it can be effective to have mystery), but eventually the audience should know where we are and who’s in the scene.

In Jaws, the scene is set quickly. A group of young adults is having a party on the beach. Steven Spielberg focuses on two of the party-goers through close-ups. They’re the main characters in the scene.

2. Catalyst

Now we need our inciting incident, a beat that kickstarts the plot in the scene. This is when the two lovers-to-be decide to split off from the rest of the party and run along the beach.

3. Rising action

Now that the action has begun, it’s time to escalate things. Stakes start to get raised, tension is built.

In Spielberg’s opening scene, this is when the girl decides to go into the water. The audience is starting to get uncomfortable – the ocean at night? Scary.

Action continues to rise when Spielberg shoots the girl from below. Something is lurking. Stakes are getting higher.

4. Climax

The climax is the moment we’ve all been waiting for, the peak of the action in the scene. The argument reaches its core, the hero deals a final blow, the will-they-won’t-they couple kisses, etc.

In Jaws, this is when the girl is attacked. The scene has been building to this.

5. Catch your breath

This part is optional – sometimes you want to cut away right at the climax. But having a moment to settle can also be useful, some time to say, “Whoa, what just happened?” How long this portion is depends on the pacing of your film.

This moment in Jaws is expertly done. Spielberg shows the drunken guy lying by the shoreline, using that beat to slow the pace and let the horror sink in before the scene ends.

Famous Film Scenes: What They Teach Us About Structure

Some of the most famous film scenes follow the exact principles we’ve outlined — perfect case studies on how to make a scene stick with audiences long after the credits roll. From the dinner table tension in American Beauty to the desert standoff in The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly, each one delivers a clear objective, conflict, and shift. When you study these moments, ask: What changes? What’s at stake?

The reason famous film scenes like this work so well is that their structure feels invisible. It grips the audience without calling attention to itself. The framework is there, but it’s all in service of character, mood, and story propulsion.

How to Write a Scene Setting

Writing a scene’s conflict

As scene examples like Election and Goodfellas have shown us, a great scene usually needs some sort of conflict. The protagonist in a scene is often overcoming something to achieve their goal.

CONFLICT DEFINITION

What is conflict?

Conflict is the confrontation of two opposing forces. In a story, conflict comes from obstacles to a given character’s goals. It may be an inanimate object (inclement weather when a character’s goal is to climb Mount Everest), or another character with an opposing goal (in a sports movie, one team wants to win, the other team also wants to win).

Of course, conflict doesn’t need to be as obvious as a guy having an all-out brawl with a dog… But it can be:

Something About Mary • Writing a scene example

Sure, this battle is largely for laughs, but it also makes sense as a piece of conflict. The dog is an obstacle in the way of Ted’s goal: impressing Mary. He wants to be calm, cool, and collected, but instead, he’s caught in a ridiculous battle with a tiny pooch.

Conflict often manifests in dialogue.

Take a look at this scene from Midsommar:

Writing a scene example • Midsommar

Here, Ari Aster creates a conflict that feels incredibly organic because it’s two characters who simply have two different goals. Chris wants space from Dani, and Dani wants to be close to Chris.

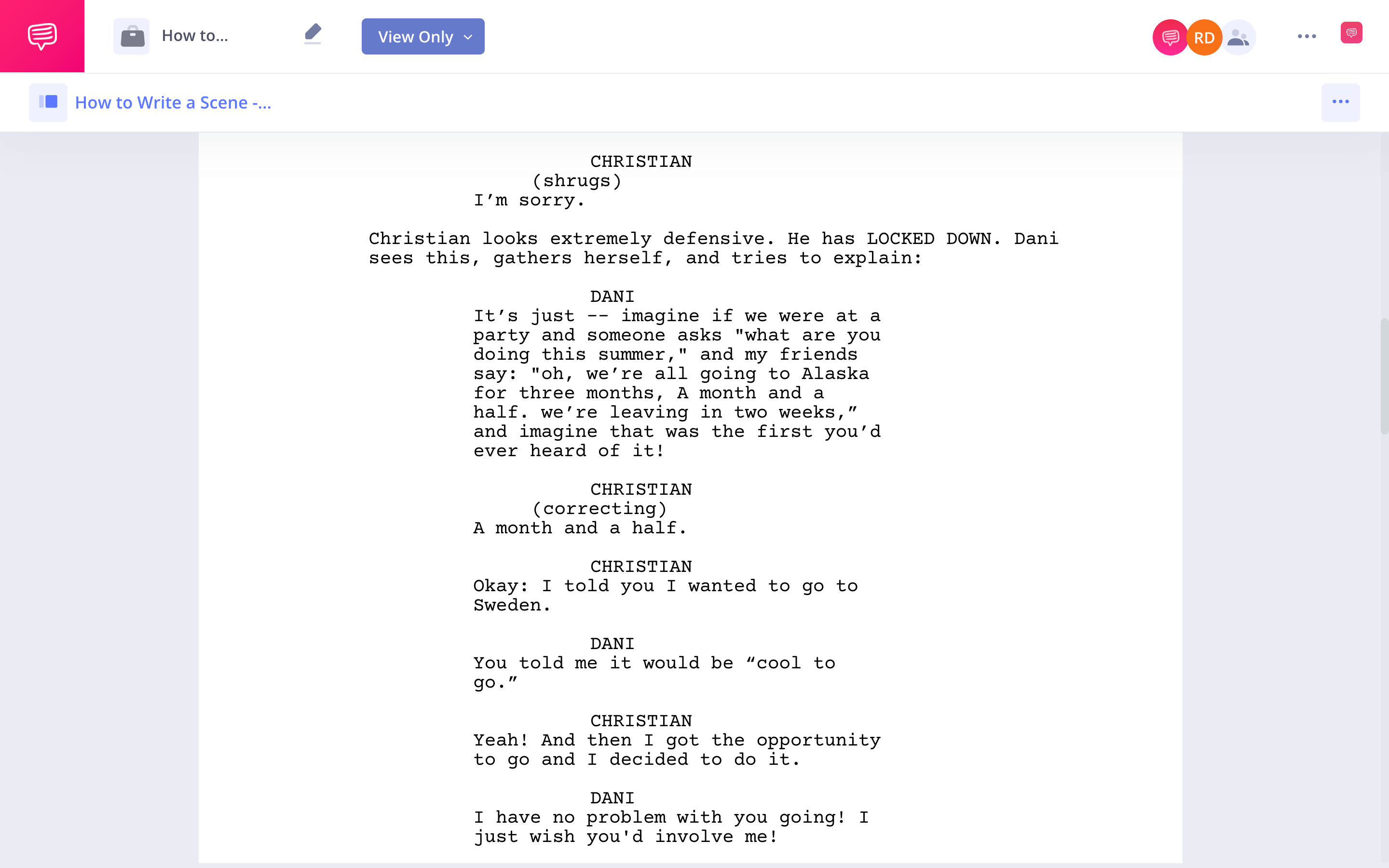

Let’s take a look at the scene on the page – we imported Aster’s script into StudioBinder’s screenwriting software:

Midsommar • Describing a scene

What makes the scene work so well is that Dani is being honest with her wants, while Christian is unable to articulate the truth: he didn’t tell her because he doesn’t want her to come.

As you can see in the dialogue, each line from the characters has these two different intentions. Dani is trying to understand why Christian wouldn’t tell her, and Christian is trying to convince her that what he’s done isn’t weird, so that he doesn’t have to say the truth.

For more on Aster's pastoral nightmare, we have written further about the symbolism of Midsommar as well as an analysis of the screenplay.

Conflict doesn’t have to be between characters: it can also come from within.

Aftersun follows Calum, a young father battling depression, and his daughter Sophie as they go on a vacation together. Throughout, Calum’s goal is clear: he wants to have fun quality time with Sophie.

And yet, in this scene, he is withholding and cruel. The superficial conflict is external: his daughter wants him to sing, and he doesn’t want to. But what makes the scene so emotionally charged is the internal conflict, which is overtaking the external conflict.

He realizes he’s making his daughter miserable, but he can’t get out of his head, which only heightens his self-hatred.

The internal conflict in this scene is part of what makes Aftersun such a beautiful and subtle portrayal of mental illness. Scenes like this demonstrate how emotional truth and restraint often lead to the best writing ever. It’s a prime example of fiction writing tips in action, where subtext, action, and silence reveal more than exposition ever could.

How to Write a Fight Scene That Hits Hard

Whether it’s an emotional showdown or a physical brawl, knowing how to write a fight scene means combining pacing, stakes, and character intention. A well-crafted fight isn’t just action — it’s storytelling through conflict. Think of the hallway scene in Oldboy or the bar fight in Kingsman: every punch has purpose. These scenes are gold standards when studying how to write a fight scene with rhythm and stakes.

Related Posts

How to Write a Scene Setting

Character development

Within a scene’s conflict comes character development, which informs your character’s arc. As Mercurio noted, most scenes result in your character going through some sort of change.

This change can be massive. Take this pivotal moment in The Lion King:

Example of scene from The Lion King

Here, the character development is pretty obvious. Mufasa’s death is a devastating blow to Simba and imbues him with a guilt that causes him to run away from his kingdom.

It also marks the beginning of his transition out of childhood.

Of course, Mufasa also has a drastic character development. He begins the scene alive and ends it dead.

Kind of the biggest change a character can experience.

Character development in a scene isn’t always so huge, nor should it be. Let’s look at this iconic scene from The Graduate:

The Graduate

During his party, Ben doesn’t seem to change much – things are mainly just happening to him. But that’s the point. He has no agency. As the scene progresses, Ben gets inundated with questions about what he’s doing next, and the claustrophobic framing indicates that Ben is feeling suffocated.

It’s not an enormous change, but it’s there, feeding Ben’s overall character arc. He’s feeling disillusioned and restless. By the time Mrs. Robinson is introduced, it only makes sense that he’s easily convinced to have an affair: he’s looking to do something different. These small psychological reveals are among the most underrated fiction writing tips—show internal change through subtle external cues.

How It Fits Into The Plot

Plot function

When writing a scene, it should come as no surprise that you should be keenly aware of its place within the story. This means thinking about character arcs, yes, but it also means thinking about the plot itself.

How is your scene moving your plot forward?

Just like with character development, the amount your scene pushes your plot forward can vary. As any writing coach will tell you, scenes that hit act climaxes must carry emotional and structural weight. Robert McKee calls scenes with the largest ramifications for plot act climaxes, because they’re usually — wait for it — climaxes of an act.

In this video, we break down the insane Act 3 climax from Joker.

Act 3 Climax in Joker

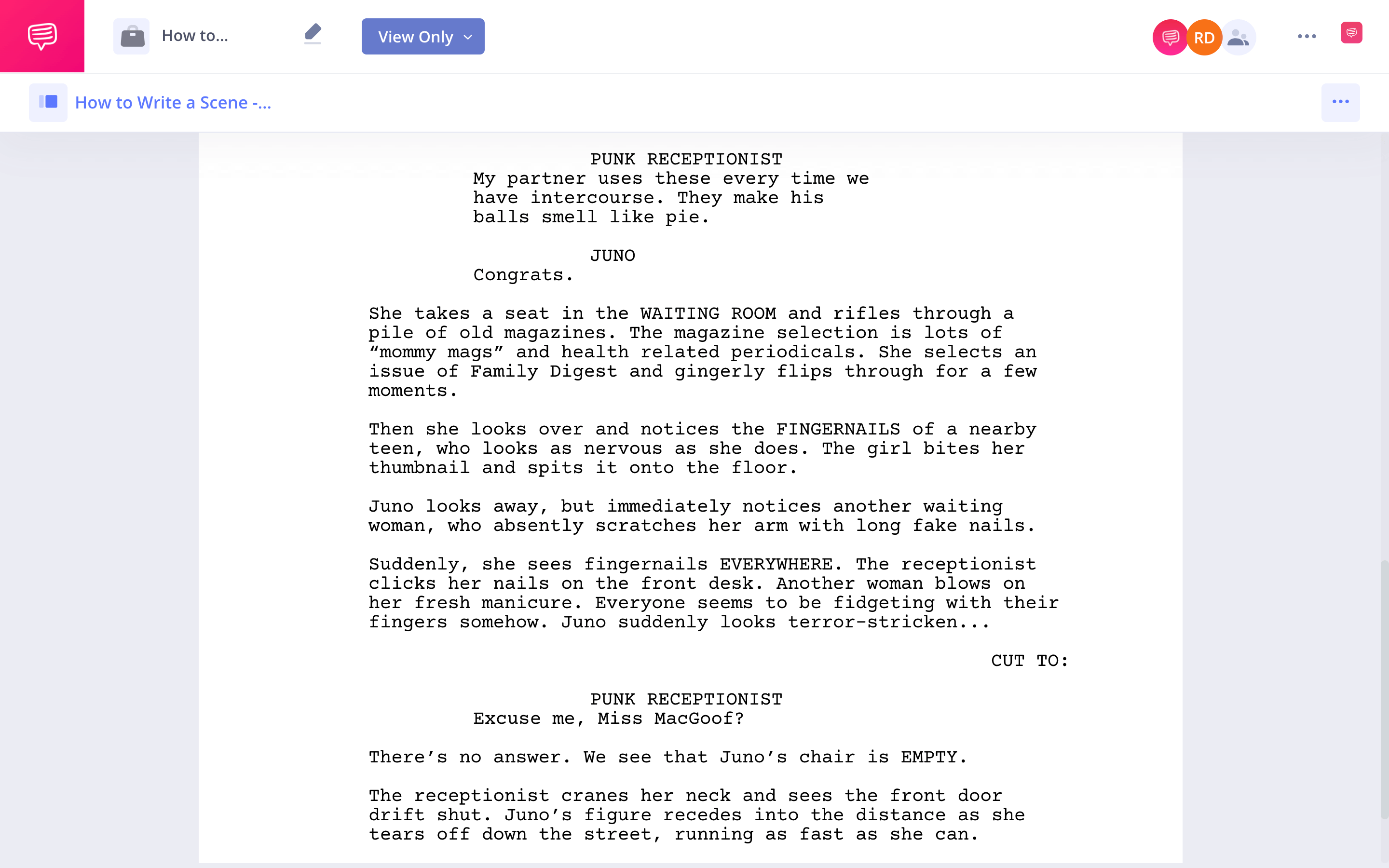

In Juno, the act climax takes place at an abortion clinic, when Juno decides that she can’t go through with the procedure. The scene works as a break into the second act of the film.

Before Juno enters the clinic, she’s told by an anti-abortion protester that fetuses have fingernails. At first, it seems like a small detail, but take a look at the end of the scene on the page:

Diablo Cody shows us how to set a scene in writing • Scene examples

Writer Diablo Cody expertly builds Juno’s internal conflict through action. Juno sees fingernails everywhere.

The pace of the writing quickens, indicating a level of panic, and culminates in an abrupt “cut to.” Juno’s left, and we’ve entered the next act: preparing to have the baby. Cody’s use of visual metaphor and pacing here is some of the best writing ever in modern screen comedy.

Scenes with slightly less impact are referred to by McKee as sequence climaxes. These are scenes with big plot points that punctuate the end of a sequence, but they’re not as consequential as the end of an act.

Take this scene from The Apartment, often heralded as one of the greatest romantic comedies of all time:

The Apartment • Scene examples

This scene comes at the end of a larger sequence within the Christmas party, where Bud and Fran are getting along swimmingly. The major plot point comes near the end: when seeing Fran’s mirror, Bud realizes she is the woman his boss has been sleeping with. Suddenly, his prospective romantic relationship with Fran has become a lot more complicated.

Billy Wilder accentuates the realization with a great piece of creative lighting: shining a light directly in Bud’s face when he looks in the mirror.

Sometimes a scene isn’t the climax of an act or a sequence. And that’s okay! But there can still be change.

Take a look at this scene from The Talented Mr. Ripley:

The Talented Mr. Ripley • Building a scene

Just a fun romp, right? Wrong. Well, yes, it is, but there’s subtle plot work happening in this scene. Tom is becoming more infatuated with Dickie, a development which has crucial ramifications for the rest of the movie.

This kind of buildup is what makes famous film scenes land so powerfully. Think of the final speech in The King’s Speech or the hallway brawl in Oldboy—each is earned, not forced.

For the scenes that are missing certain elements, reexamine them. How can you work on the missing element? If you can’t, is the scene truly necessary?

When all is said and done, a great scene isn’t great because it follows the rules. It may just happen to follow them, but the greatness is rooted in something far more ineffable.

This level of scene analysis isn’t just for screenwriters — fiction writers and even literary agents look for scenes that pull their weight. Every piece of writing you submit should show momentum and clarity of intent.

Writing a great scene can feel overwhelming, but don’t let these tools bog you down. Let your instincts guide you—then refine. Whether you’re trying to make a scene that grips the reader or create a scene for your novel, short film, or screenplay, remember: every strong scene builds toward something meaningful.

Related Posts

Up Next

How to structure a screenplay

Alright, now you know how to write a scene. But knowing how to write a scene isn’t the end-all be-all. If your scene isn’t formatted correctly, however, it’s not going to matter– most people will stop reading. Learn how to format using our examples and templates.

I'm planning to film in 7 months and these videos are so helpful to me. Thanks!